A Week in Slovakia

Notes and stories from a week in a country in the centre of Europe, but perhaps on the periphery of the world and continent’s attention.

In May I spent a week in Slovakia, visiting friends who came into my life through other friends and the serendipity of my peripatetic life. I had, however, first heard of the country 22 years ago when I met a Slovak friend in high school in New York (who I reconnected with after two decades on this trip). My imagination at that age and the limitations I placed upon it could not envision a future where I would visit this country. It felt distant and opaque - a place that existed in stories and anecdotes rather than a living, breathing entity. Perhaps we feel this way about several parts of the world and then fuelled by curiosity, the hinges to the doors of discovery loosen and we find ourselves there.

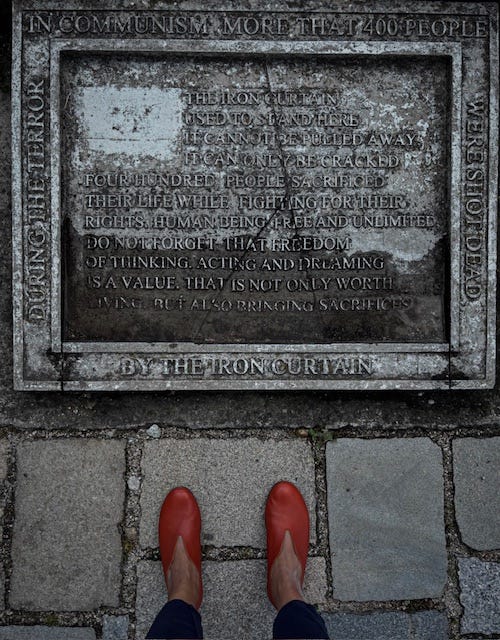

There I was in a relatively young landlocked country in the centre of Europe (quite literally), but perhaps on the periphery of the world and continent’s attention. Slovakia’s storied history is also a window into the course of European history with multiple epochs of invasion and occupation - Roman, Byzantine, Franco, Ottoman and, in the past century, Germany and the USSR. This is evident architecturally, culinarily and also in how people navigate their sense of self and belonging. Slovakia’s geostrategic significance as the frontier of the Iron Curtain, is best understood in Devin, a village on the outskirts of Bratislava situated at the confluence of Morava and the Danube River, which flow in opposite directions. Just a stone's throw from the ‘West’ (Austria), Devin became both the symbolic and literal edge of the Iron Curtain. It is a haunting place. At the foothill of the castle ruins is a memorial: a bullet-ridden gate that commemorates 400 individuals who were shot while trying to cross the river to freedom during the Cold War.

The week was spent between Bratislava, hiking in the High Tatras, and Central Slovakia. I was in Bratislava for a brief yet impressionable time. More than three decades on from becoming a sovereign state and gaining independence from the Communist regime, the physical legacy of the Cold War period still has an imprint on the streets, in contrast to the classical harmony of the Hapsburg era architecture in the Old Town and the modern high rises that have sprung up in recent years including an expensive apartment building designed by the late Zaha Hadid.

Bratislava is the only capital city in the world that borders two countries (Hungary and Austria). Over the years I had heard from friends and acquaintances in London that they would often fly to Bratislava enroute to Budapest because it was a cheaper travel option. A place to pass through but not to linger in. For me Bratislava was not a transit point to a grander city, it was the starting point of a journey to see the breadth of the country. It was also a city that several friends call home so perhaps my vantage point was different. So much of travel for me is not the quest for the remarkable and the dazzling, but noticing the familiar in a different place and time – how people greet each other in the morning, shop for groceries, what music plays in bars and restaurants.

We arrived in the Tatras one evening after a 3.5-hour drive from Bratislava through rolling hills and dense forests. On the way we ate mutton goulash and deep-fried sheep cheese in an establishment just off the highway which was situated within a farm. The next morning after fortifying ourselves with eggs, pancakes, and semolina porridge from the maximalist hotel buffet we set off on a hike (moderately difficult by my parameters but for friends who grew up there, it was a saunter) in the High Tatras, part of the Carpathian Mountain range, that straddle the border of Poland and Slovakia. We arrived at Zelené Pleso, an emerald-green alpine lake at 1550m elevation, surrounded by snow-tipped jagged peaks swaddled by clouds. On the ascent we saw wildflower-filled meadows, fields of blooming yellow rapeseed flowers, and pristine waterfalls. In the mountains there is no landmark to fix your gaze upon, and this makes it difficult to orientate yourself. There is an undeniable sense of surrender, of being enveloped by a majestic entity. You feel you have arrived at a place where the boundary between the tangible and the sublime has grown porous.

At our accommodation in the Tatras, which also had an art gallery, I was introduced to the paintings of celebrated Slovak artist Mária Medvecká, whose work spans four decades beginning just after WWII. Her paintings capture the people and landscape of her native Orava, a rural region in northern Slovakia. Much changed in the world and in the country in those decades but Orava, through the eyes of Medvecká, remained timeless. Her canvas is small, and the brushwork is precise and expressionistic. The palette is characterised by ruddy browns, murky greens and beige. Medvecká also introduces light in some of the paintings, thereby enlivening them. Any work of art is evidence of the material circumstances in which it was produced and Medvecka’s work is no different. Historically, Orava was a poor agrarian region with harsh winters, and the frugality is on display within the frame. The fields and hills are sparse barring the occasional hardy farmer tending to his produce. Upon return to London I tried to seek out more material about Medvecká’s life and artistic sensibilities but very few resources in English come up online.

From the Tatras we made our way to Central Slovakia to stay at a friend’s cottage that has been in his family for 40 years. In the heart of the country are several cities that were important mining regions for gold, silver, copper, and iron. One of those cities is Banská Bystrica where my friend was born and spent her early years. It is also home to the Memorial and Museum of the Slovak National Uprising, which commemorates one of the largest armed campaigns against Nazism in Europe that began in the city. The museum is housed in a Brutalist building with modernist geometry consisting of two curved halves that resemble the cap worn by sheep herders. In the centre between the two wings stands a large bronze sculpture entitled ‘victims warn us’, consisting of a group of tangled figures lying sideways with legs stretched out and a smaller group of men standing above them. An eternal flame flickers at the base of the sculpture. It is impossible to visit this museum and not consider the echoes in our present moment.

At the independent cinema next to the museum was a glass window with a poster in Slovak for the upcoming screening of All We Imagine as Light. This made me smile. A joyous reminder of how wide art can and does travel. I foresaw a predominantly Slovak audience imagining the lives of Malayali nurses in Mumbai and perhaps a vision of urban India that disrupts their fantasy.

The following morning, at our friend’s cottage in a small village, I woke up to the first pink traces of daylight that smudged the sky. Outside the bedroom window, branches of a large tree loomed. If I sat on the windowsill, it almost felt like I was living in a tree. Birdsong and the bleating of goats, cows, and sheep from the farm next door were often the only sounds we heard all afternoon.

Our evenings at the cottage saw us sat around a campfire to warm our bodies and occasionally grill meat and cheese. There is a cosmic energy about gathering around the circumference of an elemental force like fire and a sense of time dilating. The winds carry laughter and banter, and before you know it the sky is cobalt, and a sliver of the moon appears. The week was a reaffirmation of the quicksilver nature of human interaction, the way that so much of the connection that flows between people may be transient, multiple, ambivalent, but ultimately very beautiful. I settled on the feeling of what it means to surrender to the simplicity of the moment, the ease of the present. A privilege and a salve in a time of much brutality including in a country that Slovakia borders (Ukraine).

At midnight we would gaze at the sky where a constellation of stars was dancing like fireflies – luminous, dazzling and elusive.

Thank you for reading and the gift of your time and attention. The best way to help Missives grow is to share it with your family, friends, and others.